Aldebaran

- Year

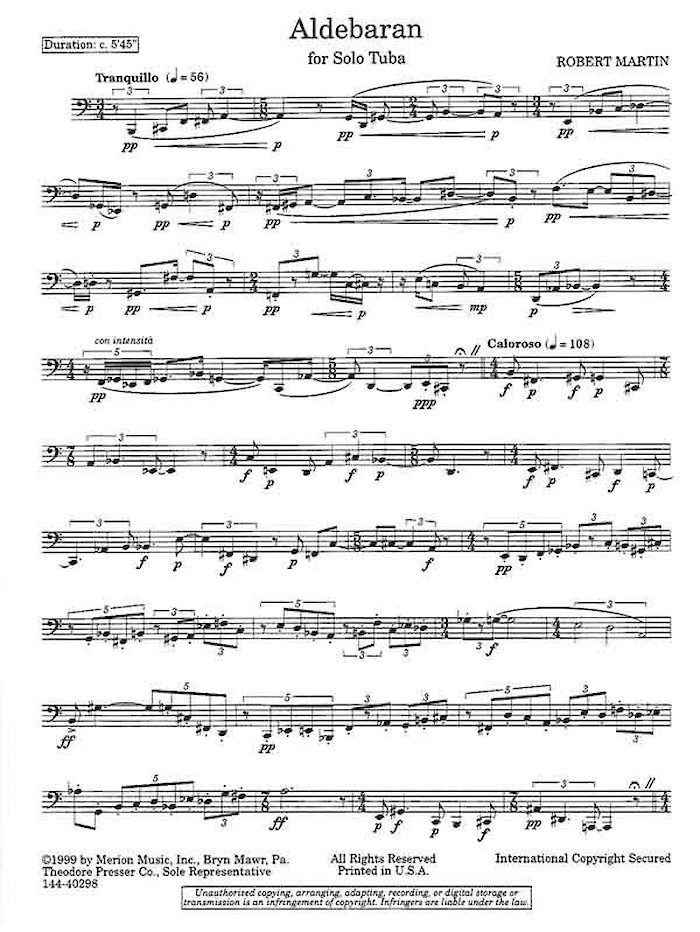

- 1994

- Duration

- 5:45

- Category

- Solo

- Instrumentation

- tuba

- Location

- Manhattan, New York

- Work Group

- The Stellar Pieces

- Group Siblings

- Purchase

- Theodore Presser

Description

Aldebaran is a solo tuba piece named after the red-orange star in the constellation of Taurus. Because of its location and color, the star has been called "the eye of the bull."

Program Notes by P. Griffiths

Star Songs

Knowledge of the stars has not dispelled their wonder. Our stories about them have altered—we see in them now huge gravitational force, immense age, vast distance and the synthesis of the atoms of which we are made, not the dotted outlines of gods, heroes and celestial animals—but that change has not diminished the awe they evoke, for our stories are as extraordinary as those of an older time.

Robert Martin’s Nine Stellar Pieces seem to belong to both times, both sets of stories. Their vigorously modernist style places them in a contemporary world of quantification, precision, and disinclination to accept received ideas without acute analysis. But their sound-poetry also pursues the stars’ ancient associations, besides taking account of their appearance—the luster that has stayed the same through the millennia, all nine subjects being among the brightest in the sky.

What would a star sound like? As points, they could only be single tones. As unchanging, they would have to be tones going on eternally. But though there are indeed some long, if not eternal, tones here, each of these pieces is essentially an extended melody: not so much the song of a star, perhaps, as a song addressed to a star, a hymn.

Each is, though, in another sense the song of a star: the star performing it. The pieces are virtuoso items, ‘stellar’ for sure, one for each of the common orchestral wind instruments, including saxophone. And wind instruments are suitable for the star-singing purpose because they are wordless voices, mouth-blown, and because of their pure colors.

The pieces were composed over a period of sixteen years, from autumn 1981 (Sirius) to spring 1997 (Achernar), and yet they are stylistically consistent and share many features. Each moves through a sequence of connected but diverse phases, defined by markings that recur from piece to piece: Deciso, Espressivo, Drammatico, Agitato, Appassionato, and the rarer Elevato (suggesting indeed a hymn-like character, present in Antares, Sirius, Achernar and Shaula) and Velato (for the ‘veiled’ sounds of clarinet or saxophone tremolos, or trumpet flutter-tonguing, all pianissimo).

The changes of pace and rhetoric are brought about by melodic developments that go right through each piece. Such developments would include repetitions and transformations of small motifs (easy to hear in Arcturus), periodic rises to progressively higher notes or falls to progressively lower ones, widenings or narrowings of intervals, revolvings around a particular interval, and varyings of phrase by keeping the rhythm much the same but altering the pitches. Very often development takes place within a context of dialogue: an idea grows, or diminishes, when it is confronted in alternation with a contrasting idea.

So much for generalities. Now some specifics on the pieces, their stars and their stories, given in the order of the recording, which is the order the composer has suggested for complete performances.

Spica for clarinet (1984). Spica, blue-white, is the brightest star in the zodiac constellation of Virgo, where it represents the spike of wheat in the virgin’s hand. The piece starts out moderately low and quiet, with gestures ending in tremolos that slip lower. Through all the subsequent changes of character, the instrument’s top register is reserved for the Tempestuoso music very near the end, reaching up finally to a high G repeated in echo. Then back, in a postscript.

Regulus for horn (1988). Regulus, also blue-white, is the brightest star in another zodiac constellation, Leo, being the lion’s heart. It gained its name, ‘little king’, from Copernicus. Much of the piece is pure song, offset by passages of stopped staccato tones, long low notes or outbursts of assertion. Finally, after the most dramatic moment, comes an extreme drop. The bass C repeated intermittently earlier had seemed low; now the instrument plumbs an octave lower.

Arcturus for bassoon (1987). Arcturus, yellow-orange, is the fourth brightest star seen from earth. It belongs to the contellation of Boötes, but its name means ‘watcher of the bear’, with reference to the neighboring constellation of Ursa Major. This the music seems to recognize, being more than usually suggestive of two voices in dialogue, one observing the other. The most fluently melodic passages focus on particular registers, and bring out the often overlooked versatility of the instrument. As in the clarinet piece, but differently, the ending is in the extremes.

Antares for trumpet (1990). Antares owes its name, ‘rival to Mars’, to its red color. It is the brightest star in the zodiac constellation Scorpius. Allusions to a warrior god and a warrior creature are surely present in the music, though the piece is more various than that would imply. It begins slow, quiet and distant, then warmer, with a nice effect of the harmon mute being slowly withdrawn (at the end of the opening section) or inserted (a little later). Decisiveness enters with staccatos and repeated notes. Then comes the Velato music, and after that the Elevato, interrupted and spurred by hurtling drama. The ending, once again, is at a high point, followed by a closing return to the start.

Sirius for flute (1981). Sirius is bright white, the brightest star we see and chief of Canis Major. Appropriate for it the bright white tone of the flute, in a sequence of scurryings, songs and ejaculations. Maybe the heart of the piece is the Elevato section that comes about two-thirds of the way through, starting with oscillations through a minor sixth. But there is a climax again right at the end, with the highest, loudest note of the piece and, three octaves under it, the lowest.

Achernar for alto saxophone (1997). Achernar is our ninth brightest star—brighter than Spica or Antares, or such other familiar objects as Betelgeuse and Deneb, but never seen from above latitude 30º north, and so invisible to nearly everyone in the United States and everyone in Europe. It was, though, seen by Arab voyagers, who named it ‘river’s end’, since it marks the end of the river constellation Eridanus. The piece, fittingly written last, has many similarities with others in the cycle: runs of accelerating notes, as in Antares and Sirius, and—very close to Spica—‘veiled’ tremolos, widening range and a near-final top note with echo. But Achernar is about endings, and the ending is unique. It is even unique twice over, since the last note of all can be played, alternatively, fortissimo.

Aldebaran for tuba (1994). Aldebaran, red-orange, is the principal star of Taurus, representing the eye of the bull. If the horn was well suited to royal Regulus and the trumpet to martial Antares, the tuba is certainly the right instrument for making bull sounds, and even bull movements: the slow repeated notes suggest an animal pawing at the ground, and the sallies near the end, from successively lower to successively higher notes, are like charges. But the tuba-bull can sing, too. Once more the ending is in extreme registers, and special.

Vega for oboe (1982). Vega, white and our fifth brightest star, is the first star of Lyra, the lyre of Orpheus and Apollo, inventors of music. Early civilizations in Mesopotamia and India, however, saw this constellation as an eagle or vulture, and the piece seems to accept both connotations. Most of it is eloquent melody, and most of it is in flight.

Shaula for trombone (1993). Shaula, a blue-white star, owes its Arabic name of ‘the stinger’ to its position at the tip of Scorpius. The piece, at the end point of the cycle, finds a new context—and a new color—for much that has been heard before: the dialogue of legato and staccato, the slow removal of a mute during a sustained note (cf. Antares), the exchanges after this between running figures in a crescendo and bold, bouncy triplets (cf. Aldebaran, quoted almost exactly), the dramatic accelerations, the middle-high register trills (cf. Spica) and, inevitably, the quick close after extremes of register have been touched, at the culmination of one more Elevato. The scorpion stings, three times, and expires.

– Paul Griffiths, 7/16/2000

Reviews

9 Stellar Pieces - Press Quotes

"...their sound-poetry pursues the stars' ancient associations...the luster that has stayed the same through the millennia." -- Paul Griffiths, Music Critic, New York Times

"Do give the disk a try, for these are highly interesting excursions into the capabilities of wind instruments." -- David Denton, Fanfare Magazine, Nov/Dec 2000

"a personal musical voice that has an instinctive relationship with each of the instruments used..." -- David Denton, Fanfare Magazine, Nov/Dec 2000

Past Performances of Aldebaran

| Date/Time | Location | Artist/Players |

|---|---|---|

| 2001-05-27, 9:00 PM | outdoor night performance, Culpeper, VA USA | Steve Forman (Steve Forman-tuba) |

| 2003-02-28, 7:30 PM | Planetarium, Michigan State University, Lansing, MI USA | Musique 21 |

| 2017-11-01 | Furious Artisans (FACD 6803), New York, NY USA | Steve Forman (Steve Forman-tuba) |